The bond market suffered a significant meltdown in 2022.

Bonds are generally thought to be the boring, relatively safe part of an investment portfolio. They’ve historically been a shock absorber, helping buoy portfolios when stocks plunge. But that relationship broke down last year, and bonds were anything but boring.

related investing news

In fact, it was the worst-ever year on record for U.S. bond investors, according to an analysis by Edward McQuarrie, a professor emeritus at Santa Clara University who studies historical investment returns.

The implosion is largely a function of the U.S. Federal Reserve aggressively raising interest rates to fight inflation, which peaked in June at its highest rate since the early 1980s and arose from an amalgam of pandemic-era shocks.

Inflation is, in short, “kryptonite” for bonds, McQuarrie said.

More from Personal Finance:

Where to keep your cash amid high inflation and rising interest rates

Workers still quitting at high rates — and getting a big bump in pay

Here’s the best way to pay down high-interest debt

“Even if you go back 250 years, you can’t find a worse year than 2022,” he said of the U.S. bond market.

That analysis centers on “safe” bonds such as U.S. Treasurys and investment-grade corporate bonds, he said, and holds true for both “nominal” and “real” returns, i.e., returns before and after accounting for inflation.

Let’s look at the Total Bond Index as an example. The index tracks U.S. investment-grade bonds, which refers to corporate and government debt that credit-rating agencies deem to have a low risk of default.

The index lost more than 13% in 2022. Before then, the index had suffered its worst 12-month return in March 1980, when it lost 9.2% in nominal terms, McQuarrie said.

That index dates to 1972. We can look further back using different bond barometers. Due to bond dynamics, returns deteriorate more for those with the longest time horizon, or maturity.

For example, intermediate-term Treasury bonds lost 10.6% in 2022, the biggest decline on record for Treasurys dating to at least 1926, before which monthly Treasury data is a bit spotty, McQuarrie said.

The longest U.S. government bonds have a maturity of 30 years. Such long-dated U.S. notes lost 39.2% in 2022, as measured by an index tracking long-term zero-coupon bonds.

That’s a record low dating to 1754, McQuarrie said. You’d have to go all the way back to the Napoleonic War era for the second-worst showing, when long bonds lost 19% in 1803. McQuarrie said the analysis uses bonds issued by Great Britain as a barometer before 1918, when they were arguably safer than those issued by the U.S.

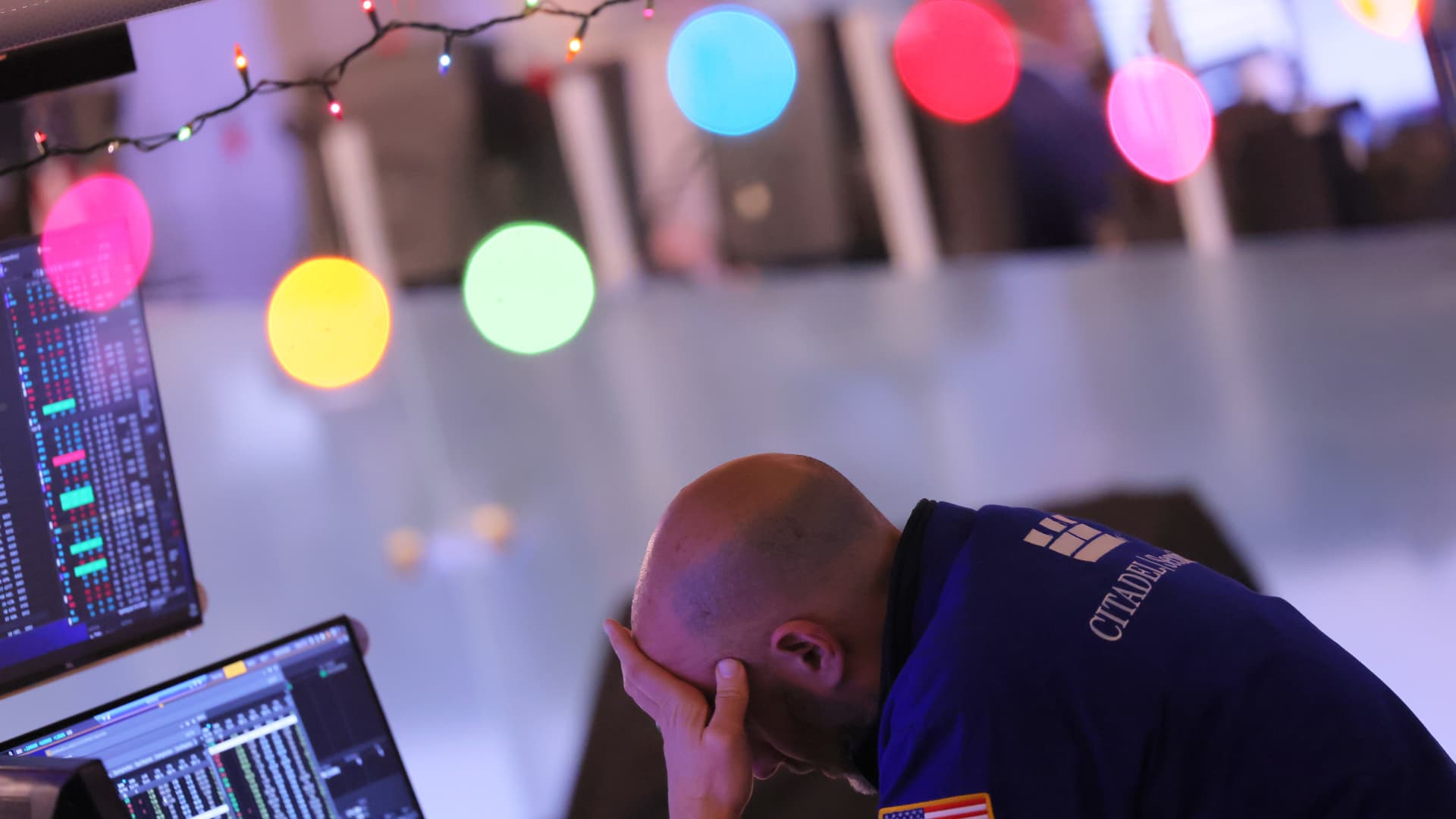

“What happened last year in the bond market was seismic,” said Charlie Fitzgerald III, an Orlando, Florida-based certified financial planner. “We knew this kind of thing could happen.”

“But to actually see it play out was really rough.”

Why bonds broke down in 2022

It’s impossible to know what’s in store for 2023 — but many financial advisors and investment experts think it’s unlikely bonds will do nearly as poorly.

While returns won’t necessarily flip positive, bonds will likely reclaim their place as a portfolio stabilizer and diversifier relative to stocks, advisors said.

“We’re more likely to have bonds behave like bonds and stocks behave like stocks: If stocks go down, they may move very, very little,” said Philip Chao, chief investment officer at Experiential Wealth, based in Cabin John, Maryland.

Interest rates started 2022 at rock-bottom — where they’d been for the better part of the time since the Great Recession.

The U.S. Federal Reserve slashed borrowing costs to near zero again at the beginning of the pandemic to help prop up the economy.

But the central bank reversed course starting in March. The Fed raised its benchmark interest rate seven times last year, hoisting it to 4.25% to 4.5% in what were its most aggressive policy moves since the early 1980s.

This was hugely consequential for bonds.

Bond prices move opposite interest rates — as interest rates rise, bond prices fall. In basic terms, that’s because the value of a bond you hold now will fall as new bonds are issued at higher interest rates. Those new bonds deliver bigger interest payments courtesy of their higher yield, making existing bonds less valuable — thereby reducing the price your current bond commands and dampening investment returns.

Further, bond yields in the latter half of 2022 were among their lowest in at least 150 years — meaning bonds were at their most expensive in historical terms, said John Rekenthaler, vice president of research at Morningstar.

Bond fund managers who had bought pricey bonds ultimately sold low when inflation began to surface, he said.

“A more dangerous combination for bond prices can scarcely be imagined,” Rekenthaler wrote.

Why long-term bonds got hit hardest

Bonds with longer maturity dates got especially clobbered. Think of the maturity date as a bond’s term or holding period.

Bond funds holding longer-dated notes generally have a longer “duration.” Duration is a measure of a bond’s sensitivity to interest rates and is impacted by maturity, among other factors.

Here’s a simple formula to demonstrate how it works. Let’s say an intermediate-term bond fund has a duration of five years. In this case, we’d expect bond prices to fall by 5 percentage points for every 1-point increase in interest rates. The anticipated decline would be 10 points for a fund with a 10-year duration, 15 points for a fund with a 15-year duration, and so on.

We can see why long-dated bonds suffered especially big losses in 2022, given interest rates jumped by about 4 percentage points.

2023 is shaping up to be better for bonds

The dynamic appears to be different this year, though.

The Federal Reserve is poised to continue raising interest rates, but the increase is unlikely to be as dramatic or rapid — in which case the impact on bonds would be more muted, advisors said.

“There’s no way in God’s green earth the Fed will have as many rate hikes as fast and as high as 2022,” said Lee Baker, an Atlanta-based CFP and president of Apex Financial Services. “When you go from 0% to 4%, that’s crushing.”

This year is a whole new scenario.Cathy Curtisfounder of Curtis Financial Planning

“We won’t go to 8%,” he added. “There’s just no way.”

In December, Fed officials projected they’d raise rates as high as 5.1% in 2023. That forecast could change. But it seems most of the losses in fixed income are behind us, Chao said.

Plus, bonds and other types of “fixed income” are entering the year delivering much stronger returns for investors than they did in 2021.

“This year is a whole new scenario,” said CFP Cathy Curtis, founder of Curtis Financial Planning, based in Oakland, California.

Here’s what to know about bond portfolios

Amid the big picture for 2023, don’t abandon bonds given their performance last year, Fitzgerald said. They still have an important role in a diversified portfolio, he added.

The traditional dynamics of a 60/40 portfolio — a portfolio barometer for investors, weighted 60% to stocks and 40% to bonds — will likely return, advisors said. In other words, bonds will likely again serve as ballast when stocks fall, they said.

Over the past decade or so, low bond yields have led many investors to raise their stock allocations to achieve their target portfolio returns — perhaps to an overall stock-bond allocation of 70/30 versus 60/40, Baker said.

In 2023, it may make sense to dial back stock exposure into the 60/40 range again — which, given higher bond yields, could achieve the same target returns but with a reduced investment risk, Baker added.

Given that the scope of future interest-rate movements remains unclear, some advisors recommend holding more short- and intermediate-term bonds, which have less interest-rate risk than longer ones. The extent to which investors do so depends on their timeline for their funds.

For example, an investor saving to buy a house in the next year might park some money in a certificate of deposit or U.S. Treasury bond with a six-, nine- or 12-month term. High-yield online savings accounts or money market accounts are also good options, advisors said.

Cash alternatives are generally paying about 3% to 5% right now, Curtis said.

“I can put clients’ cash allocation to work to get decent returns safely,” she said.

Going forward, it’s not as prudent to be overweight to short-term bonds, though, Curtis said. It’s a good time to start investment positions in more typical bond portfolios with an intermediate-term duration, of, say, six to eight years rather than one to five years, given that inflation and rate hikes seem to be easing.

The average investor can consider a total bond fund like the iShares Core U.S. Aggregate Bond fund (AGG), for example, Curtis said. The fund had a duration of 6.35 years as of Jan. 4. Investors in high tax brackets should buy a total bond fund in a retirement account instead of a taxable account, Curtis added.